The Architects of Woodchester Mansion

Charles Hansom

Charles Hansom. Image courtesy Penelope Harris.

Charles Francis Hansom was responsible for the initial mid-1850s design of Woodchester Mansion, and built the north wing, and also the Church of the Annunciation and the Dominican monastery at Woodchester. Later in life he told his son that he regarded the Woodchester church and monastery as his best work. He also had a significant influence on the Mansion in that he provided Benjamin Bucknall’s early training in architecture.

Hansom was born in York in 1817 to a Catholic family, who had worked in the city’s building trade in the eighteenth century. He trained with his elder and better known brother Joseph (1803-82), who was also an architect, the inventor of the Hansom cab in 1834, and the founder of ‘The Builder’ magazine in 1842. Sometimes Charles Hansom’s work is incorrectly attributed to Joseph. At the start of his career Charles worked as the city surveyor in Coventry, where in 1843 he was asked to design the new Catholic church of St Osburg by the priest, Father (later to become Bishop) Ullathorne – the Catholic mentor of William Leigh. From this beginning he became a successful designer of churches, and developed a long and flourishing career as a provincial architect. For most of his life he was based in Clifton, Bristol, practising on his own until 1854, and then in partnership with Joseph in London until 1859. After this he went to Bath, and then back to Bristol with his son Edward as apprentice and, from 1867-71, as a partner. Finally he was in partnership with a former pupil, Frederick Bligh Bond, from 1886-8.

The famous architect A.W.N. Pugin had introduced and emphasised the importance of two principles in Gothic Revival architecture; the need to be historically correct to the mediaeval building traditions and to fully understand the theological tradition of the church. Charles Hansom had the skill to comply with both traditions and produced many successful (and mainly Catholic) churches. Examples include Our Lady, Hanley Swan (1846), Downside Abbey (1846), Stapehill Abbey (1847-51), Thurnham, Lancs (1847-8), St Anne Edge Hill Liverpool (1848), Coughton, Warwickshire (1851-3), Ampleforth Abbey (1855-7) and St John, Bath (1861-3). He was asked to produce designs for Catholic churches in Australia and sent out two basic designs to New South Wales in 1846-8. These were based on his churches at Thurnham, Lancs and St Osburg’s, Coventry and adapted locally as necessary. Later (1851-3) he sent five model designs to Australia for churches in the State of Victoria. He was also responsible for the Catholic Cathedral of St Francis Xavier in Adelaide, which was funded by William Leigh.

An interesting building by Charles Hansom – the Grade II listed Giraffe House at the old Bristol Zoo. Similar to many of his designs for local houses, but with a door two storeys high!

By the late 1860s the requirement for Catholic churches was declining; possibly Hansom was a victim of his own success, certainly in the West Country. He then developed his business in schools and colleges, starting with Ushaw College library (in conjunction with his brother Joseph, 1851), followed by, amongst others, Clifton College, (Big School 1862, Chapel 1865, Percival Library 1875), Malvern College (1863-5) and Kelly College Tavistock (1877). In 1879 he produced the first buildings for University College Bristol, and also did much work for the Bristol Schools Board, and designed the Giraffe House at Bristol Zoo. He was a fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects, and died in Clifton in 1888.

Benjamin Bucknall

Benjamin Bucknall, the principal architect of the Mansion, was a local man, who grew up in Rodborough on the outskirts of Stroud. He was the fifth of the seven sons of Edwin Bucknall (1791-1869) and his wife Mary (1802-74). He was initially apprenticed to a millwright; his mother was related to the Clissold family who had long been in the woollen trade in the Stroud area. Through the influence of a family friend Benjamin and his two younger brothers converted and became Roman Catholics. Bucknall was confirmed in the Church of the Annunciation at Woodchester on 2nd May 1852. He met William Leigh through the church, and Leigh noted the young Bucknall’s interest in mediaeval art and crafts. Leigh arranged for Bucknall to be articled to Charles Hansom, who in the 1850s was completing work on the Dominican Priory at Woodchester and commencing plans for the Mansion.

Bucknall’s signature appears on many of the drawings for the Mansion from the Hansom brothers office in the latter part of the 1850s. He seems to have taken responsibility for the design around about 1860. The clock tower bears the date 1858, and he made the drawings for the chapel. Initially his role may well have been to fit out the interior details of parts of the building already designed externally by Hansom. Construction of the house proceeded through the 1850s and 1860s, as Leigh’s finances permitted. Both William Leigh and Benjamin Bucknall shared an admiration for the work of the significant French architect, Eugene Emmanuel Viollet le Duc. Bucknall’s interest in le Duc’s work is said to have arisen when he came across le Duc’s Dictionnaire Raisonne de l’Architecture Francaise in William Leigh’s library. He learnt French in order to understand le Duc’s writings, and became one of the few British architects to promote le Duc’s style.

One of Bucknall’s early commissions, probably obtained through his association with the Hansom brothers, was the church of St Wulstan, Little Malvern.

While working on the Mansion, Bucknall was also establishing himself as an architect, designing houses and churches. In 1858 the foundation stones of the Catholic churches of Our Lady and St Michael at Abergavenny and St George’s Taunton were laid. These were followed by many others. St Wulstan’s, Little Malvern (1862) has a rose window of similar design to Woodchester. The convent of St Rose of Lima, Stroud, is based on Ste Chapelle in Paris. Bucknall made improvements including a new porch at the Anglican church of Holy Trinity, Slad in 1869. He extended St David’s Church in Swansea, built by Charles Hansom, and also designed the Neo-romanesque Seamen’s Church in Swansea. The church of the Poor Clares of Baddesley Clinton, near Knowle, Warwickshire was built when Bucknall was, for a short while, in partnership with T. R. Donnelly of Birmingham, and was consecrated in 1870. Also in 1869-70, Bucknall collaborated with Edward Welby Pugin, son of the famous Augustus, at Bartestree Convent in Herefordshire.

Holy Trinity, Llanegwad.

A fine example of Bucknall’s mature work is found at the Anglican Church of Holy Trinity, Llanegwad, Carmarthenshire. It was built for the wealthy industrialist Charles Henry Bath, and started in 1865, but his unexpected death delayed the completion until 1878. The design incorporates both Gothic and Romanesque features. The exterior is simple, with a slender spire, and the interior has a barrel vaulted roof and is beautifully decorated, with stained glass windows and wall paintings. It is well worth a visit, but check opening times before travelling.

Stone gutters, chimneys and air vents at the Mansion.

As well as working on the Mansion, Bucknall designed many smaller houses on Leigh’s estate and in the surrounding area. The lodge at Scar Hill, near the top entrance to Woodchester Park, is an example. St Stephen’s, Nympsfield, is another. He also produced the larger Tocknells Court, near Painswick, which has a double spiral staircase, the outer one for the family and the inner for the servants to pass up and down unseen. He built West Grange at Stroud for his friend Dr Charles Wethered in 1866. This has many of the characteristics of the Mansion. Bucknall’s style included extensive use of stone where possible, even for the down pipes and gutters, which are often held up by stone brackets. Some chimneys are round in the French style and often are smoothly integrated with the chimneystacks, with flues are used as features on the outside of the building. Bucknall was also fond of the external staircase wing (though does not use this on the Mansion). Windows often have a hipped arch and the quatrefoil air ventilators are a Bucknall ‘trademark’. It was said that the stonemasons in Stroud enjoyed carving for Bucknall.

Bucknall’s ‘trademark’ quatrefoil air vent – a three dimensional logo found on many of his buildings, large and small.

Benjamin Bucknall married the 23 year-old Henrietta Mary Hungerford King on May 1st 1862. She was the daughter of Charles King, a physician. The marriage took place in the Roman Catholic Chapel of St Felix in Northampton, and was conducted by the bishop, Francis Kerril Amherst. The following year their first child, Mary Josephine, was born in Stroud, followed by Charles Edward in 1864, Edgar in 1868 and Beatrice in 1870. None of the children married. The eldest, Josephine, found fulfillment as a nun in St Rose’s Convent in Stroud, where she was educated, and lived to be 100. Edgar died in 1889, and Charles was in the Merchant Navy.

In about 1863-4 the Bucknall family moved to Swansea, settling in Oystermouth. The port and the closeness of the S. Wales coalfield meant that Swansea was an expanding area, and Benjamin’s younger brothers Robert and Alfred were already there working as architects and builders. As well as the churches in the area, Benjamin Bucknall worked on new buildings for Swansea Grammar School, which are still in use.

Seven letters from Benjamin Bucknall to Viollet le Duc survive in the le Duc archives. In the first of them, written in 1862, Bucknall praised and admired le Duc’s work and asked for advice on obtaining a good glass maker for the glazing of the chapel at Woodchester. He also discussed gargoyles, and hoped that in the future le Duc’s architectural works would be available in English. He made several visits to Viollet le Duc’s buildings in France, and met the French architect. In 1876 Bucknall and his friend Charles Wethered stayed with Viollet le Duc in Switzerland. By this time Bucknall had started translating some of Viollet le Duc’s books on architecture into English. How to Build a House, described by le Duc as an “architectural novelette”, appeared in 1874, and in a second edition two years later. Annals of a Fortress appeared in 1875 (reprinted 2009) and The Habitations of Man in All Ages in 1876. A work on the geology of Mont Blanc was published in 1877, following the Swiss visit, along with the first volume of the Discourses on Architecture. Volume II of the Discourses appeared in 1882 and a revised complete edition in 1889. The latest reprint (sometimes translated as Lectures in Architecture) was published in February 2010. Bucknall’s translation of the Discourses is said to be significant because it enabled American architects like Frank Lloyd Wright to be influenced by Viollet le Duc’s ideas.

Bucknall’s 1874 design for a new house for Willie Leigh.

After William Leigh’s death in 1873, Bucknall was asked to produce plans for completion of Woodchester Mansion, and for a new and smaller residence as shown in his sketch (above). In 1878 The Cottage was further improved for Leigh’s son, Willie. The photograph below shows the characteristic ventilators, staircase wing and chimney design. At this time, Bucknall wrote to Willie Leigh expressing his feelings about the unfinished Mansion: …for there is nothing more sad to the sight than an unfinished work – it is even more forlorn than the ruin of a building which has served its purpose and gone to decay… Believe me that these remarks are only suggested by a sincere interest in a place which is associated with many happy days.

‘The Cottage’, the Leigh family home for sixty years.

In the winter of 1877-8, Bucknall visited Algiers for his health. At the time Algiers was a popular place for Europeans to visit in winter. He moved there permanently the following year, and earned his living designing and renovating beautiful white villas in the Moorish style. It is a measure of his talent as an architect that he was able to change so completely and successfully; he was well known in Algiers and a road, the Chemin Bucknall, was named after him. His children visited him in Algiers; none of them ever married. His elder son Charles was with him when he died there in 1895, and the funeral was very well attended. He is buried in the English and French cemetery, with a tombstone erected as a token of esteem and regard by some of his friends, and a memorial plaque in the English church, praising him as an Architect of Rare Genius and Taste and describing him as The disciple of Viollet le Duc.

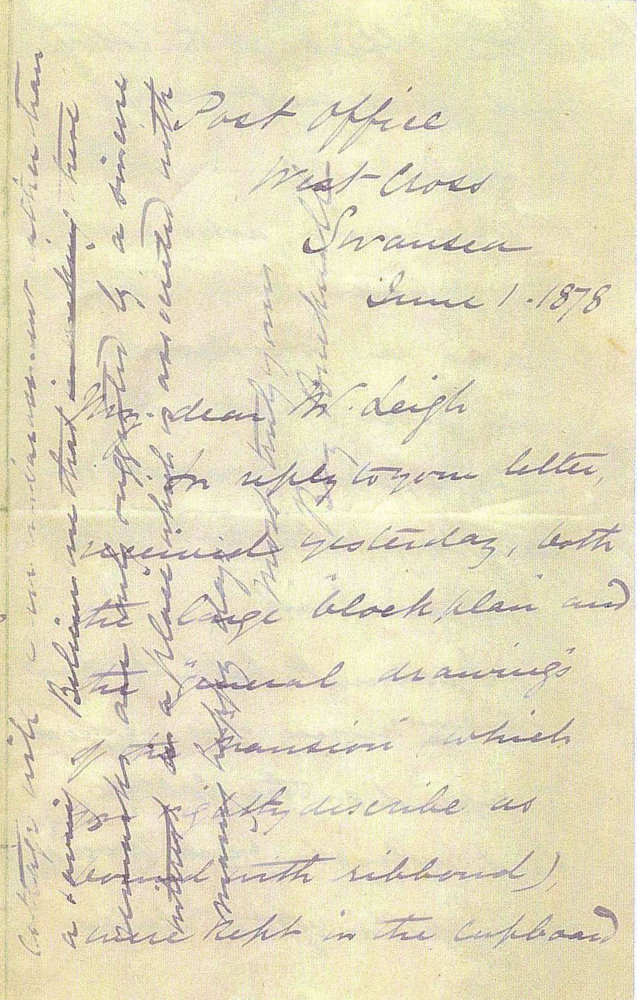

Bucknall’s 1878 letter to Willie Leigh about Woodchester Mansion.

Please note: all images on this page ©Woodchester Mansion Trust, not to be used without permission.

2025 Open Day Season

We will be open 11am - 5pm every Friday, Saturday, Sunday and Bank Holidays from Friday 4th April to Sunday 2nd November.

Telephone 01453 861541

Woodchester Mansion,

Nympsfield,

Stonehouse,

Gloucestershire

What3Words nuns.skill.respected